NLG Legal Observer documents riot police

by Patrick Young

Lawyers and legal workers have played an important role in movements for social change for as long as courts and lawyers have existed. Movement lawyers have played important roles in challenging unlawful government repression of social movements, challenging unjust laws, and providing legal defense for movement participants facing prosecution from the state. There is perhaps no more direct or visceral confrontation between people and the state than the criminal prosecution process wherein the defendant and the state are formally named as opposing parties.

This is the fourth segment in the Lawyers, Lockboxes and Money series, a project that explores the role shared social movement infrastructure has played in social movement uprisings and how this infrastructure has evolved over time, moving across issue areas and geographies to knit together a shared fabric of progressive social movements.

The longest-standing institution doing this work in the United States is the National Lawyers Guild (NLG). The NLG was founded in 1937, during Roosevelt’s New Deal, as an organization of lawyers to offer a counterweight to the conservative positions being taken by the American Bar Association (ABA). The invitation to the group’s founding meeting invited lawyers to discuss the formation of an organization of “…all lawyers who regard adjustments to new conditions as more important than veneration of precedent, who recognize the importance of safeguarding and extending the rights of workers and farmers upon whom the welfare of the entire nation depends, of maintaining our civil rights and liberties and our democratic institutions.”[1] In its early years the Guild coordinated legal work among lawyers for the burgeoning labor movement, represented accused communists target by the House Committee on Un-American Activities and the red scare, and organized to oppose the rollback of civil liberties during World War II.

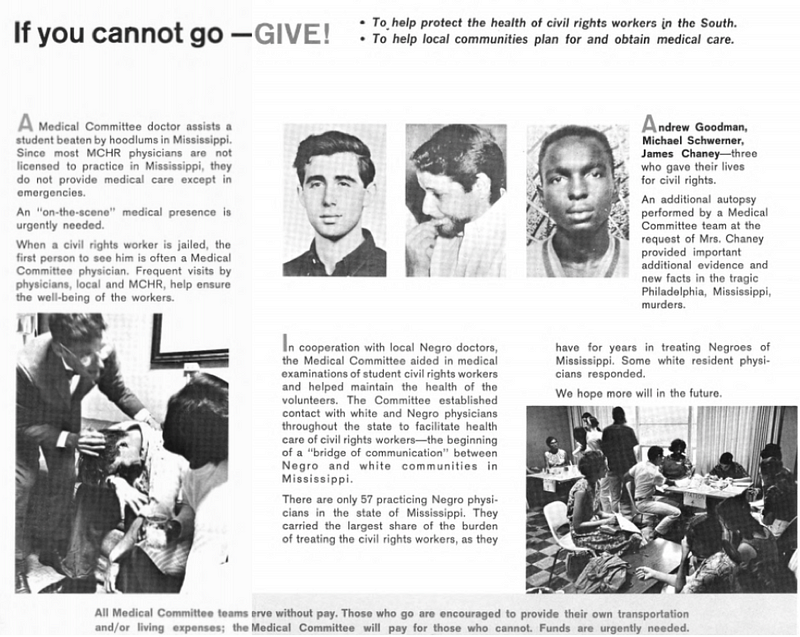

In 1964, the NLG formed the Committee for Legal Assistance to the South, to organize volunteers to travel to Mississippi to support the Civil Rights Movement. This marked the beginning of a shift within the organization from being a professional organization of lawyers to increasing its role as a social movement infrastructure institution. Writing a history of the Guild at its 50th anniversary, Rabinowitz and Ledwith remarked, “The Guild’s accomplishments in the South were many, but none was more important than its initial commitment to provide legal aid to an historic movement before it became a national cause.”

Over the next several years, the NLG played an increasingly active role in supporting organizers in the free speech movement and the movement against the war in Vietnam. Michael Ratner, a student anti-war activist who later became the president of the Center for Constitutional Rights observed that the guild was different from other legal groups because, “it not only defended people opposed to the war, it condemned the war and stood in solidarity with the Vietnamese people.”[2] The Guild also recognized the role of non-lawyers in its movement work. In 1970 delegates at its national convention voted to open membership to law students, strengthening the organization’s ties with the student movement. The next year the Guild voted to open its membership to non-lawyer legal workers and “jailhouse lawyers.” Over the next several decades, the NLG would continue to play a significant role in supporting activists in the anti-nuclear movement, the Central American solidarity movement, the and the LGBTQ movement during the AIDS epidemic.

But legal work in social movements is not limited to litigation. A particularly important function that has emerged in wave after wave of movement uprisings is organizing legal support for activists targeted with arrest and prosecution. Importantly, much of the work of organizing to support large numbers of people facing arrest, tracking defendants through the booking and bail process, raising funds for legal defense, collecting evidence, and providing material and emotional support for defendants through the legal process and during incarceration, is political and organizational work that is often performed by activists who are not lawyers.

Alongside the representational legal work performed by movement lawyers, movement organizers established parallel support structures to train movement activists on their legal rights, track and support arrestees through the arrest and booking processes, raise funds to support legal defenses, and mobilize public and political support in favor of activists targeted for arrest and prosecution. When activists were targeted with particularly serious charges and sentenced to long prison terms, support committees would be tasked with organizing to provide political and emotional support for political prisoners, raise funds to support their families and their defenses, and support released political prisoners in their re-entry. Historically, these structures have been uniquely strong and well formed in the struggle for Black Liberation and the American Indian Movement — two movements that were targeted for particularly severe state repression.

Mass Legal Defense

More recently, legal support organizing structures have emerged to proactively prepare for mass arrests with legal workers prepared to support targeted activists across social movement spaces. In the aftermath of the 1999 WTO protests in Seattle, Washington, the Direct Action Network (DAN) Legal Team supported movement lawyers and arrestees in preparing 600 cases for trial. In addition to supporting lawyers with legal research and evidence gathering, the legal team distributed press releases, organized rallies and press conferences, and mobilized to fill courtrooms for trials.

Shortly after the WTO, the DAN Legal Team reestablished itself as the Midnight Special Law Collective. At the April 16 protests of the IMF and World Bank in Washington, DC in 2000 Midnight Special organized ‘know your right’ trainings for more than 1,500 activists, trained 200 legal observers and organized local progressive attorneys who were prepared to take cases of arrestees. In total 1,200 people were arrested over three days at the 2000 IMF and World Bank meetings. Over the next ten years, Midnight Special would train legal workers and provide legal support for thousands of arrestees in major mobilizations around the US and Canada.[3]

Local legal collectives largely modeled after — and often trained by — the Midnight Special Law Collective emerged in different cities around the country during periods of major protest. In the lead up to the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq, Midnight Special organizers helped to form the Legal Support to Stop the War Collective (LS2SW). In the lead up to the 2008 Republican National Convention, members of the Midnight Special Law Collective traveled to Minneapolis to spend six weeks with local legal organizers, helping to form the Cold Snap Legal Collective.

By 2010, Midnight Special decided to disband, writing in a communique, “We have reached various conclusions: that we have been unable to break out of the service provider model; that we are dissatisfied with jumping from action to action, and leaving little infrastructure behind; that we often emulate the oppressive structures we seek to change; and that these problems are much harder to solve than we had believed.”

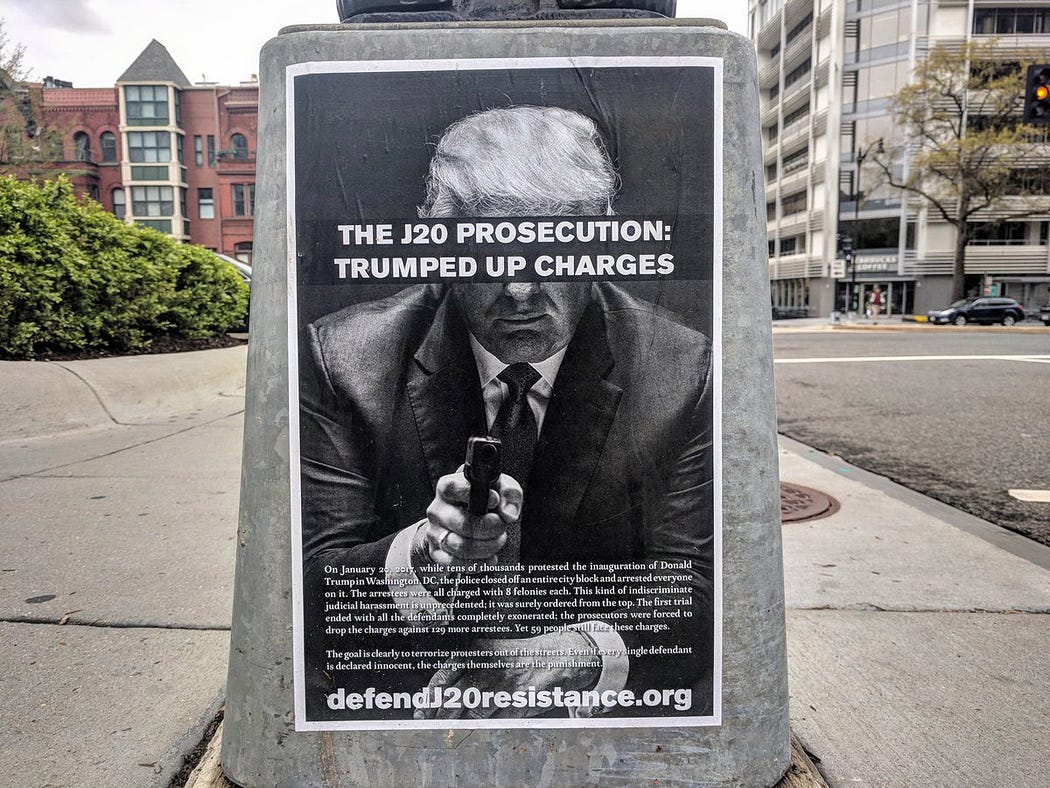

While Midnight Special is no longer organizing as a collective, it remains an important movement resource. More than nine years after disbanding, Midnight Special’s website (www.midnightspecial.net) is still live and its materials are widely circulated and used by movement organizers. Additionally, veterans of Midnight Special continue to participate in legal support in major recent mobilization including the Ferguson uprising,[4] Standing Rock, and the Inauguration of Donald Trump.

The landscape of legal workers supporting movement mobilizations is now mostly informal, but tightly networked. The NLG Mass Defense Committee listserve offers a space to broadly exchange needs and opportunities for legal workers. Many of the legal support organizers with experience coordinating legal infrastructure for large mobilizations have long histories of working together through intense situations at earlier mobilizations and rely on direct contacts and personal relationships to mobilize each other across different movement space over time.

Tilting the Scales

More recently, another movement infrastructure organization that has emerged is the Tilted Scales Collective. Tilted Scales is a small anarchist collective whose work “has involved support during all stages of a person’s case — from arrest through trial and into post-conviction appeals and long term support during a person’s time in prison.” Tilted Scales has organized webinars and speaking tours on their goal setting framework and worked with defendants and their support committees to organize for a political criminal defense.

This work has helped to fill an important gap in movement legal support work. While the lawyers representing activists facing serious charges are generally experts in the law, many do not have experience with collective action or social movements. Dylan Petrohilos who had his home raided and was charged with multiple felonies for his role in organizing protests of President Donald Trump’s inauguration said the support provided by Tilted Scales was invaluable. “They helped to contextualize the political implications of organizing my legal defense. They gave me feedback and support through the whole process. Working with them felt like a security blanket.”[5]

“The legal system is designed to be hyper-individualistic, and defendants are making decisions in a framework of uncertainty,” said an organizer from the Tilted Scales Collective. It is not uncommon for lawyers to encourage their defendants to take cooperating plea deals that involve informing on comrades or portraying their clients as “good protesters” as a way of distancing them from “bad protesters.” One of the roles of the Tilted Scales Collective, organizers say, is “preparing defendants to push their lawyers to create legal defenses that will help them achieve their goals for the charges they’re facing.”

In 2017, Tilted Scales published a Tilted Guide to Being A Defendant, a “guide for people who are seriously entangled in the criminal legal system, whether they are facing federal felony accusations, conspiracy charges, terrorist enhancements, or potential years or decades in prison.”[6] The Tilted Guide offers political defendants a framework for setting and balancing personal, political and legal goals; suggestions on working with lawyers, codefendants, and support committees; and advice on resolving cases and, if needed, surviving prison.

As our social movements become more powerful and pose increasingly credible challenges to existing power structures, we can anticipate an acceleration in the repression of dissent. Throughout history, the state has responded to the growth of radical and revolutionary movements with surveillance, infiltration, violence, aggressive prosecution and incarceration. In just the past few years, hundreds of people arrested in Ferguson, Standing Rock, the inauguration of President Trump and dozens of other actions have been charged with serious felonies. If our movements hope to continue to increase our capacity to create disruption and challenge entrenched and unresponsive elites, we will also need to invest in our collective capacity to support each other through challenging and often long legal processes — from arrest, though prosecution, and incarceration.

[1] Rabinowitz and Ledwith, “A History of the NLG 1937 to 1987.”

[2] Rabinowitz and Ledwith.

[3] “Midnight Special Law Collective — History,” accessed April 4, 2019, http://www.midnightspecial.net/history.html.

[4] Arielle Klagsbrun, Interview with author, March 17, 2019.

[5] Ellis, Interview with author.

[6] The Tilted Scales Collective, A Tilted Guide to Being a Defendant (Combustion Books, 2017).