by Patrick Young

This is the third segment in the Lawyers, Lockboxes and Money series, a project that explores the role shared social movement infrastructure has played in social movement uprisings and how this infrastructure has evolved over time, moving across issue areas and geographies to knit together a shared fabric of progressive social movements.

Over the past decade, people across the US and around the world have taken to the streets in wave after wave of popular uprising. They have camped out in city centers and remote construction sites through hot summers and cold winters. They’ve faced down militarized police forces with their chemical weapons, fire hoses, tasers, clubs, and rubber bullets. And in each of these uprisings, teams of medics have mobilized alongside protestors, warriors and protectors, to keep our movements health and safe and in the streets.

DC Medic Collective

Medics don’t run and medics don’t lead.

Others are happy to rush forward while medics are busy trying to make sure everyone gets there alive.

Medics see what our movements collective mistakes and loses look like and have to wash it of our clothes some days. Yet still we strive to not lead we won’t tell warriors and protectors to stop and go back to camp, to pray more, that is not our role.

We say, ‘those goggles suck for pepper spray, here take these.’

We strive for informed consent in all our interactions, so we strive to train people to be ready for the worst as we train to be ready for the worst.

We say, ‘hey look a trap, let’s go they’ll need help.’

We walk at your back and to your side so you know your bravery and willingness to risk yourself is not without support.

We want to help build the world we want with y’all so we strive to demonstrate that a better world is possible every time we set up a clinic out of nothing or gather to provide the best care to those typically denied.

We literally will run ourselves down to nothing till we are burnt out and sick and will still strive to take care of others first.

But still…

We stand with our brothers, with our sisters, with our family of all genders and orientations for the land, for the people and for the water.

— Noah Morris

Television footage of street medics in protests often invokes images of medics flushing protests’ eyes after they have been exposed to chemical weapons or providing trauma care to protesters struck by rubber bullets or police batons. Certainly, this is an important aspect of providing medical care in social movements, but the vast majority of medical issues that arise during mobilizations are the much less dramatic issues that often arise when large groups of people are together for long periods of time: dehydration, fainting from low blood sugar, trips and falls, heat stroke, and frostbite.

Medical workers have been mobilizing to participate in contentious politics since at least the Spanish Civil War. American doctors and nurses mobilized alongside the Abraham Lincoln Brigades to provide medical support for the Republicans. During that war, the doctors and nurses would make significant advances in battlefield surgery and front-line blood transfusions. They also pioneered a tradition of medical workers mobilizing in their skills in support of contentious politics.[1]

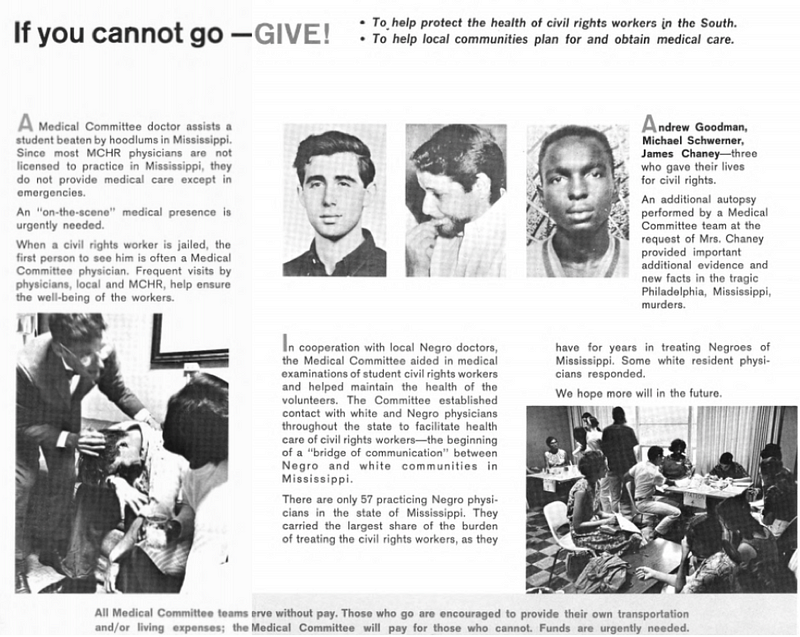

During the civil rights movement, the Medical Committee for Human Rights (MCHR) mobilized doctors, nurses, dentists, psychologists, and social works to travel to the deep south to provide medical care in poor Black communities and support civil rights workers. A brochure that the MCHR distributed to doctors emphasized the need for doctors. “An ‘on-the-scene’ medical presence is urgently needed. When a civil rights worker is jailed, the first person to see him is often a Medical Committee physician. Frequent visits by physicians, local and MCHR, help ensure the well-being of the workers.”[2] Importantly, MCHR volunteers also worked to improve access to primary care for Blacks and poor whites in the south developing rural health centers and mobile health units, health education programs, and support for community workers in developing health and medical programs.

Medical Committee for Human Rights

In 1973, two veterans of the MCHR, Ben “Doc” Rosen and Ann Hirschman took what they had learned in the civil rights movement to South Dakota to support the American Indian Movement at Wounded Knee. Rosen stayed with the AIM for the entire 71-day occupation and was shot in the arm by US Marshals. Hirschman traveled in and out of Wounded Knee along with other medical volunteers. During her time there, she operated without anesthesia on a patient who had been shot in the back of the head. She was able to stabilize his airway, keeping him alive for four days until he succumbed to his injuries. [3]

In 1999, Rosen traveled to Seattle to lead street medical trainings for what would become a new generation of street medics. Longtime street medic Noah Morris observed, “after Seattle, there was a recognition that medics were needed in urban organizing… The number of major actions that took place during the global justice movement allowed new medics to develop a lot of skills and experience very quickly.”[4] In the early years of the twenty-first century, street medic collectives emerged in many major cities across the country.

While many roles in social movements require few specialized skills, providing medical care safely and effectively requires training and there are massive differences in training levels and capabilities of medical workers. Today, medic collectives and networks of medics take different approaches to the work depending on their local circumstances, but there are some widely shared norms among the street medic community. Generally, medic collectives require volunteers to have at least 20 hours of training (these courses are typically offered over three days) to ensure that everyone offering medical assistance has a reasonable base of knowledge. Medical professionals who have much more extensive training in their field are generally expected to participate in an eight-hour “bridge training” to learn the common norms and shared practices used by street medic collectives and learn how to effectively provide medical care during street protests.[5] The Paper Revolution Collective publishes a relatively comprehensive and regularly-updated street medic guide that can augment this in-person training.

Street Medic Wiki

These basic levels of training, however, cannot equip medic volunteers for all situations. Noah Morris observed that when medics with limited training go into challenging situations, they can create more on support structures. “We’ve got to be realistic about what we can offer. Twenty hours of training isn’t going to help much in a desert.” Before inviting volunteers to join medic teams or healer councils, organizers typically go through a process of vetting potential volunteers to assess their skills and check in with movement references who can vouch for their trustworthiness.

Today there are as many as 44 action medical collectives operating in the US, but as almost entirely volunteer-based organizations, the capacity and consistency of these collectives and clinics varies drastically, ranging from well-established and high-functioning collectives with years of experience to smaller, loosely-formed networks with just a handful of volunteers with limited skills. Unions of healthcare workers have also organized workers with specific skill sets to support social movements. In October of 2016, National Nurses United deployed a team of registered nurses through its Registered Nurse Response Unit, a national network of volunteer direct-care RNs to North Dakota to support the Standing Rock Medic and Healer Council.[6]

Responding to Disasters?—?and Everyday Disasters

Organizing to provide medical support for social movements fighting for environmental, economic, and racial justice during periods of mobilization quite naturally illuminates the ongoing crisis facing the millions of people who lack every day medical care in their communities. While advocating for access to quality healthcare within the existing healthcare system, many medics are taking direct action to provide the care that their communities need.

In Chicago the all-Black Ujimaa Medic Collective came together in 2014 after a young person suffering from a gunshot wound died on the way to the hospital on the other side of town. “The fact that he was shot just a few blocks from one of the biggest and best hospitals in the country, and died on the way to another on the other side of town seemed to add grievous insult to grave injury.”[7] Since 2014, Umedics has offered more than 100 trainings in urban emergency first response to more than 1,000 people. They also offer trainings on preventing and responding to asthma attacks.

Another important approach to continuing and expanding the work of developing social movement infrastructure is deploying social movement infrastructure to provide disaster relief. In New Orleans, after Hurricane Katrina, the Common Ground Collective mobilized social movement infrastructure organizations and networks to provide food and medical support in the 9th Ward long before federal officials were on the ground. In the months following the storm, Common Ground established a medical clinic, a legal clinic, a food distribution operation, and recruited volunteers to gut hundreds of houses to allow residents to return.[8] In the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, Occupy Sandy deployed much of the infrastructure that had been developed to support the Occupy Wallstreet movement to mount a massive relief effort well before FEMA or the Red Cross made it into the communities hardest hit by the storm.[9]

The Mutual Aid Disaster Relief (MADR) network has emerged as an important space for promoting and supporting this work.[10] Founded by veterans of Common Ground, Occupy Sandy and other relief efforts MADR has organized trainings for new relief workers, helped to coordinate mutual-aid based relief programs in the wake of dozens of storms and other disasters, and developed a clear political analysis around the role of mutual aid disaster relief in the face of the climate crisis.

As the frequency and severity of superstorms increases, more and more communities are likely to experience catastrophic disasters. When the state struggles to respond, democratic and horizontally organized movement infrastructure can fill that gap and support communities as they respond to those disasters. Deploying the infrastructure created by social movements to support communities in helping themselves and each other can provide much needed relief, dramatically improving?—?or saving?—?peoples’ lives while at the same time filling the vacuum left by the state’s failure to respond with systems and practices that are directly democratic and rooted in commitments to mutual aid, sustainability, and collective liberation.

[1] Richard Rhodes, Hell and Good Company: The Spanish Civil War and the World It Made, Reprint edition (Simon & Schuster, 2016).

[2] “The Medical Committee for Human Rights” (Medical Committee on Human Rights, 1965), https://www.crmvet.org/docs/64_mchr.pdf.

[3] Kelsey Whipple, “Meet Colorado’s Activist Medics, a Rogue Band of Good Samaritans | Westword,” Westword, April 17, 2012, https://www.westword.com/news/meet-colorados-activist-medics-a-rogue-band-of-good-samaritans-5116354.

[4] Noah Morris, Interview with author, April 2, 2019.

[5] Paper Revolution Collective, “Street Medic Guide” (Paper Revolution Collective, 2018), http://www.paperrevolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Street-Medic-Guide-Paper-Revolution-v6.pdf.

[6] “Registered Nurse Response Network Sends Nurse Volunteers to Assist with First Aid at Standing Rock,” National Nurses United, October 10, 2016, /press/registered-nurse-response-network-sends-nurse-volunteers-assist-first-aid-standing-rock.

[7] “ABOUT US,” Ujimaa Medics (blog), accessed June 15, 2019, https://umedics.org/about-us/.

[8] scott crow and Kathleen Cleaver, Black Flags and Windmills: Hope, Anarchy, and the Common Ground Collective, 2nd ed. (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2014).

[9] Alan Feuer, “Where FEMA Fell Short, Occupy Sandy Was There,” The New York Times, November 9, 2012, sec. N.Y. / Region, https://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/11/nyregion/where-fema-fell-short-occupy-sandy-was-there.html.

[10] Mutual Aid Disaster Relief, “About Us,” Mutual Aid Disaster Relief (blog), accessed May 13, 2019, https://mutualaiddisasterrelief.org/.