by Patrick Young

— Part II of the Lawyers, Lockboxes and Money series

Every mobilization, every blockade, every march depends on a complex network of movement infrastructure that will likely never make it to the front page of the papers. To make all of these things possible, hundreds of people prepared and served food, organized legal support, set up medical clinics, designed websites, facilitated trainings, organized transportation, secured meeting spaces, maintained databases, and took on dozens of logistical tasks that allowed movements to operate.

The Lawyers, Lockboxes and Money series is a project that explores the role shared social movement infrastructure has played in social movement uprisings and how this infrastructure has evolved over time, moving across issue areas and geographies to knit together a shared fabric of progressive social movements. In this segment we look at the networks and organizations that provide one of the most basic infrastructural tasks movements need to take on?—?feeding people.

Fueling the Movement

Feeding people during mobilizations, particularly for activities lasting more than a few hours, is one of the most basic infrastructural needs to be encountered by social movements. All over the world, the practice of preparing and sharing food plays an important role in displaying hospitality, sharing culture and cultivating relationships. It is not surprising, then, that the organizations and networks that provide food for social movements share a rich legacy and history.

Many of the kitchen collectives currently organizing providing food for social movement mobilizations can trace their histories to two long-standing (and often intertwined) institutions?—?Food Not Bombs (FNB) and Seeds of Peace?—?both of which emerged from the anti-nuclear movement of the 1980s.

Photo Credit: Occupy Eugene

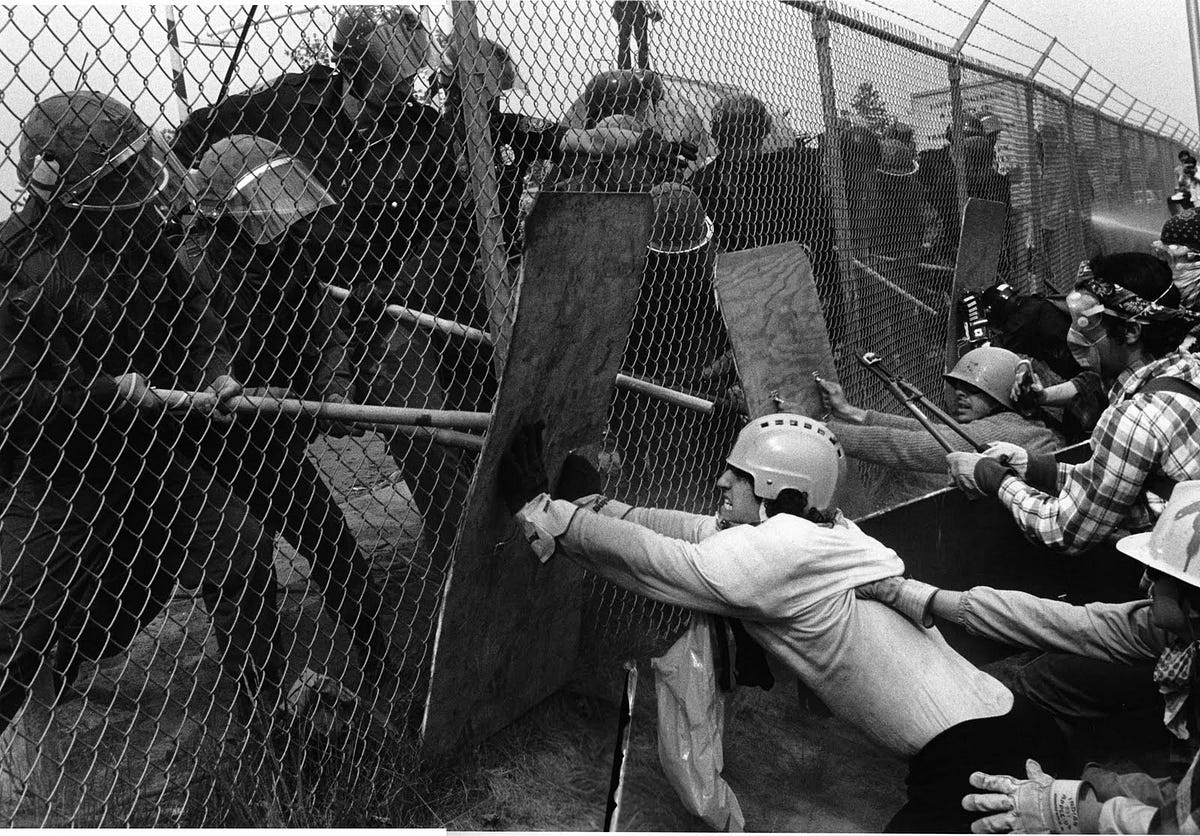

Food Not Bombs is a network of all-volunteer collectives that serve vegetarian and vegan meals for free in public squares and parks in cities around the world. It was started by Keith McHenry and C. T. Butler, two activists who had been deeply involved in the movement against the construction of the Seabrook Nuclear Power Station in New Hampshire. In 1981 the two helped to organize a protest at the annual shareholder meeting of First National Bank, one of the major financial backers of the Seabrook Power Station. In their history of the Food Not Bombs movement, McHenry and Butler laid out their plan for the action. “As nuclear-power protesters, we wanted to do street theater that would remind people of a 1930s-style soup kitchen, to highlight the waste of valuable resources on capital-intensive projects such as nuclear power while many people in this country went hungry and homeless.”[1]

The two initially planned to recruit actors to fill out the soup line but then they realized they could recruit people who were actually hungry and homeless to participate. McHenry and Butler collected day-old bread and salvaged produce from the local food coop and cooked a large bowl of soup. During the shareholder meeting over 100 people turned out for the meal. The event was an incredible success. The Food Not Bombs frame proved to be so salient that serving free salvaged food in public places as a protest of the massive spending on nuclear infrastructure became a staple in the anti-nuclear movement’s repertoire of contention.[2]

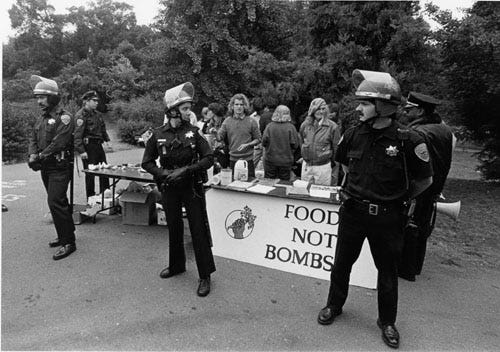

Michael Maher Photography

By 1988, Food Not Bombs groups had spread to Boston, San Francisco and Washington, DC. In May of that year, the San Francisco chapter decoupled their food servings from other actions and started holding weekly servings in Golden Gate Park, offering free healthy food for poor and hungry people. While this fulfilled the charitable function of feeding hungry people, Heynen observed that these food servings also acted “to expose poverty to the glare of those who do not want it to exist.”[3]

The next summer solidified a major shift in the political nature of Food Not Bombs. In 1989, after a decade of austerity and at the peak of urban disinvestment, people experiencing homelessness organized major tent cities in urban centers around the country to protest the crisis of homelessness. Food Not Bombs chapters in New York and San Francisco offered mass food servings at these camps and became deeply involved in organizing in support of them. By this time, Food Not Bombs had developed a robust political analysis around poverty, hunger, food security, and public space.[4]

FoodNotBombs.net

In less than a decade a group of anti-nuclear activists that had initially planned to recruit actors to participate in a soup line as a street theater action developed into an organization that was organizing around homelessness and regularly risking arrest while serving food in public parks. In 1992 Food Not Bombs held its first international gathering with representatives from 30 active groups in the US and Canada.[5] At the meeting, Food Not Bombs established its three foundational principles: “1. Always vegan or vegetarian and free to everyone. 2. Each chapter is independent and autonomous and makes decisions using the consensus process. 3. Food Not Bombs is not a charity and is dedicated to non-violent social change.”[6]

Throughout the 1990s, Food Not Bombs chapters continued to form around the US and worldwide. In addition to serving free food in public parks, Food Not Bombs chapters often contribute to social movement infrastructure by providing food during actions and movement events. In 1999 when the global justice movement burst onto the scene during the protests of the World Trade Organization summit in Seattle, Washington, members of different Food Not Bombs chapters, primarily from the US and Canada traveled to Seattle to gather, cook and serve food to the thousands of people who took to the streets during the multi-day mobilization.

The other principal nucleus of social movement institutions providing food at mobilizations is Seeds of Peace. Seeds also traces its history to the anti-nuclear movement, emerging out of the Great Peace March for Global Nuclear Disarmament in 1986?—?a nine-month, 3,700-mile march from Los Angeles to Washington, DC to raise awareness about the growing dangers of nuclear proliferation. The group of activists that came together to provided food, water, medical support and other logistics for the march recognized the important role that this type of logistical infrastructure could play in social movements and decided to form a permanent collective.[7]

Continuing its anti-nuclear work, Seeds developed a relationship with the Newe (Western Shoshone) who were demanding an end to nuclear testing at the Nevada Test Site and the return of their historic homelands. Later, Seeds organized food and other support for the Dineh (Navajo) elders in their fight against forced relocation and became deeply involved in Earth First! forest defense campaigns.

While Food Not Bombs established a network of chapters organized regular food servings in their communities and could be mobilized in support of actions, from the start, Seeds was much more focused on building infrastructure to support mobilizations. In addition to food, Seeds of Peace organized to provide medical and logistical support and direct action trainings in support of mobilizations, campaigns, and action camps, often building out the logistical core of movements and mobilizations. During Redwood Summer in 1990, a three-month mobilization in northern California to protect old-growth redwood trees from logging, Seeds of Peace organized nearly all of the core infrastructure for the campaign. That summer, when labor and environmental organizer Judi Bari’s car was bombed, she was on her way to the Seeds of Peace house in Oakland.[8]

When Hurricane Katrina hit the gulf coast in 2005, scott crow, a co-founder of the Common Ground Collective published a national call to action inviting volunteers to come to New Orleans to provide relief where the government would not. Food Not Bombs organizers were among the first to answer that call. crow writes, “a Food Not Bombs chapter from Hartford took the initial risk to get hot food into people still stranded in the waters across the river in the Seventh and Ninth Wards. The Red Cross would not go there. We knew people on the other side needed water, food, and medical attention immediately.”[9] Over the next several months, dozens of Food Not Bombs and Seeds of Peace activists traveled to Common Ground to participate in the relief efforts.

Common Ground Collective

In the first two decades of the twenty-first century, Seeds of Peace, Food Not Bombs and a wide range of similarly structured kitchen collectives would provide food support for mobilizations and other movement events around the country in a wide range of different organizational formations. While these organized collectives could deploy mobile kitchen equipment and experience in feeding thousands of people thousands of people in mass mobilizations settings, they would generally integrate large numbers of local activists to provide the labor to actually prepare meals.

Seeds of Peace identifies their role as something of a facilitator. “It is our intention to use our skills and equipment, not merely to provide a ‘service,’ but to promote individual empowerment and community solidarity by providing an effective and adaptable framework. As a small collective, we cannot, by ourselves, cook for 5,000 people. But by providing kitchen equipment and a certain level of experience, we can work with and facilitate a group of people to cook, deliver and serve a meal on such a scale.”[10]

Kitchen Crews Emerging Organically

While Seeds of Peace and Food Not Bombs have played an incredibly valuable role in supporting movements and uprisings, movements and communities often organically develop the capacity to provide food as movements emerge. In Ferguson, Missouri, in the aftermath of the murder of Mike Brown, Cathy “Mama Cat” Daniels, a retired grandmother went looking to find a way to help out. “I asked, ‘what can I do?’” she told the Huffington Post. “They said a little home-cooked meal wouldn’t hurt nothing, so I went home, and the next day I came back with spaghetti and salad and garlic bread. After that, every day I fed them. Every day.”[11] Daniels would continue serving food through the weeks of protests and the non-indictment. Later on, volunteers from Seeds of Peace would travel into Ferguson to support Daniels, particularly during the Ferguson October mobilization and the resurgence of activity following the announcement of the non-incitement.

During the mobilization to stop construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock the task of feeding the thousands of water protectors who had converged in North Dakota brought together a wide arrangement of kitchen collectives. There, water protectors organized at least 13 different kitchens across the three main camps to feed the thousands of people who were living at Standing Rock. The main kitchen was coordinated by a vegan chef named from the Netherlands who had worked with a collective of vegan chefs in Greece that cooked meals at refugee camps for 8,000 people a day. Another kitchen was staffed by Seeds of Peace volunteers, yet another was led by Brian Yazzie, a Navajo chef and chef de cuisine at the Sioux Chef, a Minneapolis-based catering company that works to revitalize Native American food culture.

Photo Credit: Brian Yazzie

Elizabeth Hoover from the Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance (NAFSA) observed that preparing traditional indigenous foods became culturally and politically important to the movement. “Traditional foods are considered an important tool in, and motivation for, winning this fight against polluting fossil fuels. Getting traditional foods into camp to keep morale up?—?whether that was enough buffalo meat in the stews across camp, or more tribally specific delicacies… was an important focus.”[12]

Stepping Up Stepping In

The participatory aspect of preparing and serving food at mobilizations has acted as a useful tool for absorbing new activists and providing opportunities for people to meaningfully participate in creating the mobilizations they are participating in. Kim Ellis, an organizer with the RAMPS Campaign said, “it’s just easy to plug into this work. It’s a way for people without a lot of experience to get involved… When you are doing something concrete you know you can be useful.”[13]

While some roles in an uprising require complex skill sets and long-term commitments, nearly anyone can help out in a kitchen, washing dishes or chopping vegetables. Involving volunteers in cooking food and washing dishes helps to bridge the gap between the people attending or participating in mobilizations and the people who are organizing them and making them happen. Ellis also observed that the landscape of organizations and collectives organizing to provide food for social movements has expanded. “It’s not just Seeds anymore. There are lots of kitchens being formed. Lots of people are doing this work all over the place.”

[1] C. T. Butler and Keith McHenry, Food Not Bombs, Revised edition (Tucson, Ariz.: See Sharp Press, 2000).

[2] Nik Heynen, “Cooking up Non-Violent Civil-Disobedient Direct Action for the Hungry: ‘Food Not Bombs’ and the Resurgence of Radical Democracy in the US,” ed. Paul Routledge, Urban Studies 47, no. 6 (May 2010): 1225–40, https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098009360223.

[3] Heynen.

[4] Butler and McHenry, Food Not Bombs.

[5] McHenry, Keith, “Documenting 30 Years of Food Not Bombs,” accessed May 1, 2019, http://foodnotbombs.net/z_30th_anniversary_2.html.

[6] “Three Principles of Food Not Bombs,” Food Not Bombs, accessed May 1, 2019, http://foodnotbombs.net/principles.html.

[7] Seeds of Peace, “About Us.”

[8] Nick Stocks, Interview with author, March 16, 2019.

[9] scott crow and Kathleen Cleaver, Black Flags and Windmills: Hope, Anarchy, and the Common Ground Collective, 2nd ed. (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2014), 120.

[10] Seeds of Peace, “About Us.”

[11] Zeba Blay, “In St. Louis, This Woman Is Making A Change One Meal at A Time,” HuffPost, 54:24 400AD, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/in-st-louis-this-woman-is-making-a-change-one-meal-at-a-time_n_59ef7ebde4b0bf1f88364889.

[12] Elizabeth Hoover, “Feeding a Movement: The Kitchens of the Standing Rock Camps,” From Garden Warriors to Good Seeds: Indigenizing the Local Food Movement (blog), December 7, 2016, https://gardenwarriorsgoodseeds.com/2016/12/06/feeding-a-movement-the-kitchens-of-the-standing-rock-camps/.

[13] Ellis, Interview with author.